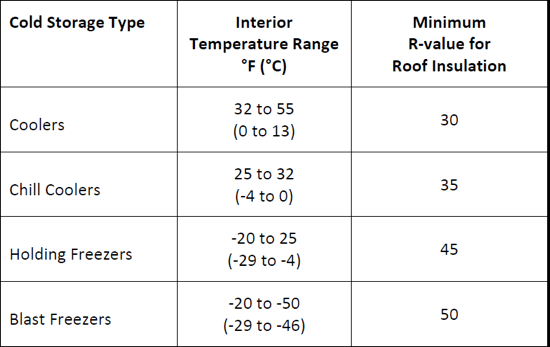

A "cold storage building" is a building or a portion of a building or structure designed to promote the extended shelf life of perishable products or commodities. There are varying levels of cold storage, such as coolers, chill coolers, holding freezers, and blast freezers. Coolers range from approximately 32 to 55 degrees F (0 to 13 degrees C), while blast freezers can have interior temperatures from -20 to -50 degrees F (-29 to -46 degrees C)1. The biggest difference from a roofing perspective is the amount of insulation for the varying levels of cold storage.

For more information register to receive CEU credits for Webinars on Demand: Click here to go to the webinars.

The primary concern for proper roof design of a cold storage building is the significant vapor drive that occurs predominantly from the warmer exterior towards the colder interior. That directly leads to two critical aspects of the roof design: 1) proper placement of a vapor retarder to manage the vapor drive and 2) proper detailing to prevent air infiltration or exfiltration at enclosure transitions and penetrations. Additionally, the reduction or elimination of thermal bridges is important because of the critical need for a highly effective thermal boundary which, of course, keeps the items within the cold storage building at the proper temperature all while using the least amount of energy.

The building science perspective

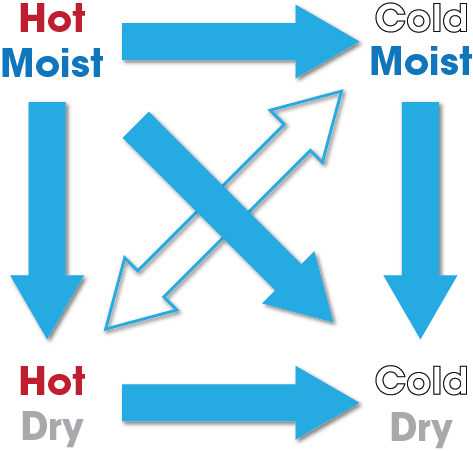

A cold storage building is an excellent example of the need to understand the basics of the second law of thermodynamics. Those principles are:

- Hot moves to cold

- Wet/moist moves to dry

- High pressure moves to low pressure

Figure 1: Illustration of the Second Law of Thermodynamics

Importantly, heat, moisture, and pressure always want to equalize across a boundary. For a cold storage building, this boundary is the building enclosure—the roof and walls.

Vapor drive and condensation

Cold storage buildings are maintained at temperatures that are most often much lower than the exterior temperature. For cold storage buildings, the warm, moist outside air wants to move to the interior of the cold storage building. This is especially the case in southern climates, and is generally true for most geographic locations in the US for most months of the year. More on that later. Therefore, the direction of the vapor drive is predominantly from the exterior to the interior. This means the roofing membrane will act as the vapor retarder and air barrier keeping vapor and air from getting into the roof system and creating condensation problems.

There may be times during the year in colder climates where the warmest cold storage buildings—a cooler with a temperature range from 32 to 55 degrees F (0 to 13 degrees C)—may experience a vapor drive from the interior to the exterior because it's colder outside than the interior. However, this is not likely problematic for two reasons. First, the amount of moisture inside a cold storage unit is low because of its low relative humidity—there just isn't a lot of moisture relative to the interior of, say, an office building. Second, because vapor drive also relates to pressure differences, a cold dry space (the interior of a cold storage unit) does not exert a pressure significantly greater than the cold, dry air of the exterior in a winter climate. Ultimately, a cold storage unit in a northerly climate should not experience a moisture gain within the roof system. And any moisture gained during the winter will be driven back into the cold storage portion during the warmer summer months.

Air leakage

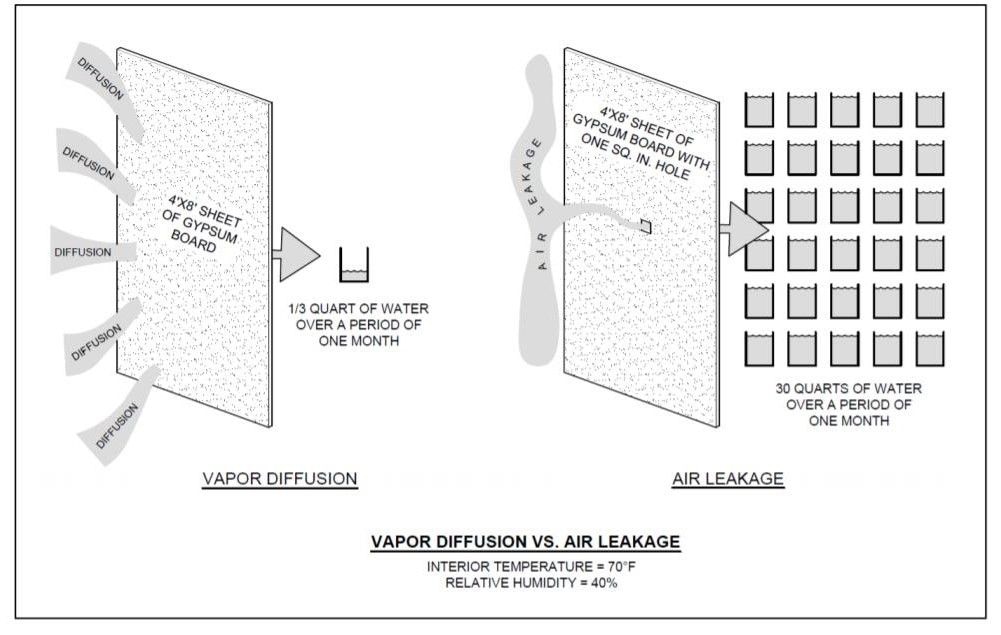

Air-transported moisture is a bigger issue than vapor drive because of the comparative amount of actual moisture transported by each process.

The National Research Council Canada collected research data that illustrated how even small openings can affect overall air leakage performance. For example, only about 1/3 of a quart of water will diffuse through a continuous 4 ft. by 8 ft. sheet of gypsum during a one-month period even though gypsum board has a very high permeance.

However, if there is a 1-square-inch hole in this same sheet of gypsum, about 30 quarts of water can pass through the opening as a result of air leakage. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 2. This example illustrates that air leakage can cause more moisture-related problems than vapor diffusion.

Figure 2: Air leakage versus vapor diffusion (Source: Building Science Corporation)

Accordingly, it is critical that a vapor retarder system be continuous when used in cold storage buildings so they also serve as an air barrier. (For more detail, see our blog about Air Barriers and Vapor Retarders). Laps, penetrations and the roof-to-wall interfaces should be sealed to prevent air leakage because discontinuity will allow air to infiltrate which can then lead to condensation problems. Again, most commonly, the roof membrane serves as the vapor retarder/air barrier.

Basic concepts of cold storage design

A cold storage building should have an uninterrupted, continuous building enclosure with these attributes:

- Adequate amounts of insulation and an appropriate attachment method to maintain interior temperature and minimize thermal loss

- Compensation for thermal expansion and contraction

- Control of air and water vapor movement

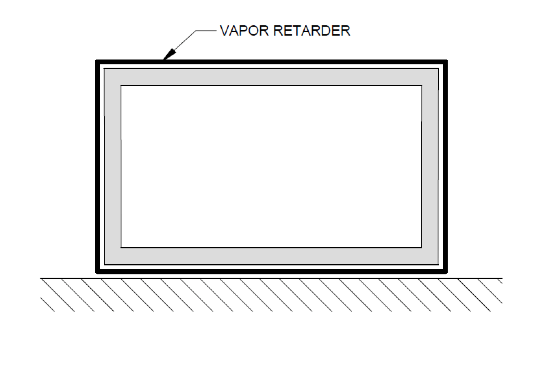

The most common way to achieve these objectives is to use an Exterior Envelope System (EES). The EES method uses a vapor retarder that is located on the exterior side of the building's structural system. More specifically, the vapor retarder encapsulates the building and is located over the roof's insulation layer, on the outside of the exterior wall's insulation layer, and under the floor. This concept is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Conceptual Diagram of the Exterior Envelope System for cold storage buildings.

Cold storage design considerations

The design and construction of cold storage buildings requires attention to the following considerations:

- Building location

- Design values

- Roof insulation

- Thermal shorts/thermal bridging

- Expansion and contraction

- Air leakage and water vapor movement

- Vapor retarder perm ratings

Building Location

In warm climates (e.g., Dallas), the prevailing vapor drive direction is inward, and therefore, the most effective location for a vapor retarder/air barrier is on the outside of the roof insulation. In most cases, the roof membrane will be the vapor retarder.

In moderate climates (e.g., Nashville and Kansas City), the vapor drive may be in either direction and the location of the vapor retarder/air barrier depends on the predominant direction of the vapor drive. However, because there is generally more total moisture in the air during the summer months (versus winter months), the predominant vapor drive is into the building. Again, the roof membrane will be the vapor retarder.

In cold climates (e.g., Buffalo), the vapor drive will be reversed when the outside temperature is colder than the interior temperature, but there is less concern with condensation issues because cold air has a relatively small amount of moisture and because the temperatures are often similar, vapor drive is less significant.

Design Values

If a roof system designer chooses to perform a dew-point or hygrothermal analysis to confirm the placement of the vapor retarder/air barrier, the following is needed:

- Interior dry bulb temperature

- Interior relative humidity

- Exterior dry bulb temperature

These values are theoretical constant values based upon design assumptions for a single point in time, yet in reality, these change from day to day and season to season.

Roof Insulation

Insulation plays a critical role in the building enclosure performance of a cold storage building. In order to minimize the potential for interior condensation, appropriate amounts of insulation should be used so the interior surfaces of the building enclosure are kept above the dew point. Insulation type and R-value selection are affected by numerous factors, such as cost, desired energy efficiency, suitable material properties, interior design temperatures, and climatic conditions. Figure 4 offers suggestions for minimum R-values for roof insulation in cold storage buildings.

Figure 4: Suggested Minimum R-Values for Roof Insulation2

The type of insulation used should be suitable and compatible for use in a cold storage building. A commonly used insulation type is closed-cell foam insulation, such as GAF EnergyGuard™ polyiso insulation. Here's a primer on roof insulation. Additionally, roof penetrations, such as mechanical curbs or roof hatches, and parapets and roof edges should be appropriately insulated and air sealed.

Thermal Shorts/Thermal Bridging

Designers should pay close attention to thermal shorts (e.g., gaps between boards) and thermal bridging (e.g., metal fasteners and plates) when designing roofing systems over cold storage buildings.

To reduce the effects of thermal shorts, roof insulation should be installed in at least two layers with offset joints—vertically and horizontally—to minimize air leakage and movement. Gaps between insulation boards should be filled.

To reduce the effects of thermal bridging, the roof membrane and upper layer(s) of rigid board insulation should be adhered. Mechanical fasteners should be avoided as the securement method for the roof membrane and upper layer(s) of rigid board insulation. When the substrate is a steel roof deck, the first layer of insulation (i.e., the layer in direct contact with the roof deck) may be mechanically attached. Subsequent layers should be installed with adhesives to reduce or eliminate thermal bridges.

Expansion and Contraction

Accommodation should be made for thermal movement in cold storage buildings. Building movement may lead to tearing of or damage to a vapor retarder/air barrier or the roofing system.

Pipes in roofs and walls may move due to thermal expansion and contraction, as well as vibration, so it is important to select pipe penetration flashings that can accommodate movement, such as pre-manufactured flashing boots.

Air Leakage and Water Vapor Movement

Problems occur when there are paths for air and water vapor movement within the building enclosure. It is imperative that the vapor retarder and roof system be continuous, tied to the wall air barrier, and completely sealed at:

- Laps and seams

- Roof penetrations, i.e., pipes, structural members, mechanical curbs, roof hatches, etc.

- Roof-to-wall interface/intersections

Limiting the number of penetrations through the roof assembly is prudent. Also, if a separate vapor retarder/air barrier is used (in lieu of it being the roofing membrane), avoid attaching the roof system through the vapor retarder with mechanical fasteners for cold storage buildings. This maintains the vapor retarder's integrity and eliminates thermal bridging from fasteners.

Special attention should be paid to steel roof decks which are used in many cold storage buildings. It is challenging to seal steel roof decks at walls and penetrations. Deck flutes can serve as "conduits" or pathways through which air and air-transported moisture can flow. To minimize these effects, flutes may be filled with closed-cell spray polyurethane foam at walls and penetration locations.

Vapor Retarder Perm Ratings

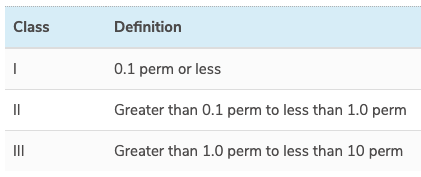

Vapor retarders are typically membranes with relatively low permeance values, but not all vapor retarders are equal. There are three classes of vapor retarder materials, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Three classes of vapor retarders

Most roof membranes are Class I vapor retarders. Perm ratings for single-ply membranes range from 0.03 to 0.06 perms. An example of a Class II vapor retarder is asphalt felts, which have perm ratings ranging from 0.3 to 0.8 perms. Examples of Class III vapor retarders are latex or acrylic paint. GAF recommends that Class I vapor retarders be used on cold storage buildings. It is important to note that these are material ratings; the full system needs to be designed and installed correctly for proper functionality.

Cold storage buildings are unique because of their low interior temperatures and the resulting vapor drive and significant potential for air infiltration. Taking into account the science of heat, air, and moisture movement when designing the roof system for a cold storage system is paramount for long-term success. For additional information, check out GAF's new document, "A Guide to Cold Storage Roof System Design"

1 "Energy Modeling Guideline for Cold Storage and Refrigerated Warehouse Facilities" issued by the International Association for Cold Storage Construction and the International Association of Refrigerated Warehouses

2"Energy Modeling Guideline for Cold Storage and Refrigerated Warehouse Facilities," issued by the International Association for Cold Storage Construction and the International Association of Refrigerated Warehouses.